Netflix Cancels Bach, Mozart, Beethoven

May 28, 2024

Roscoe, N.Y.

I’m a fan of Bridgerton (Team Penelope, if you care), the feel-good Netflix series portraying a fantastical harmoniously multiracial Regency England, and renowned for its steamy sex scenes, the marvelous Shonda Rhimes touch, and clever quasi-“classical” arrangements of pop songs. These arrangements avoid the anachronistic incongruity of 19th century sets and costumes accompanied by the disconcerting sounds of drum kits, electric guitars, synthesizers, and pitch correction.

Most of the music heard during Bridgerton episodes is composed or arranged by Kris Bowers, but sometimes during scenes where the cast assembles to dance, gossip, and flirt, the soundtrack includes music that might actually have been performed at such gatherings in the early 19th century. Listen closely to the string instruments underneath the repartee, and you might catch snatches of Bach! Haydn! Mozart! Beethoven!

After hearing some familiar music in Season 3 Episode 2 (the episode that ends with a long ——— between ——— and ———), I wondered if music credits were available somewhere. There were none at the end of the episode, but on a page on the Netflix site entitled Netflix and Shondaland Announce the Song List and Soundtrack for ‘Bridgerton’ Season 3: Part 1, I found what I was looking for.

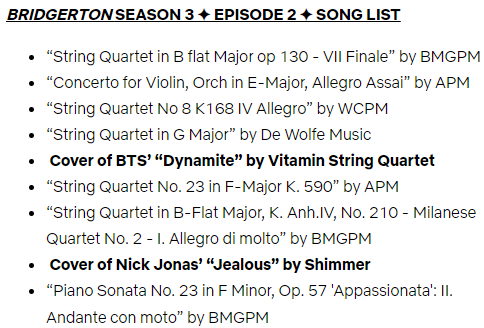

Well, not quite. Here’s the list for Episode 2:

Notice anything missing? Like, where are the composers? Who are the composers? Is there such a thing as a composer?

The composers of the music that is not printed in bold type are actually three biggies: Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven. But why are their names omitted from this list? Is Netflix deliberately cancelling these composers? Was it an oversight? Criminal negligence? Are the producers of Bridgerton not proud of using authentic period music? But what’s the point if the compositions are not properly identified? Are the producers embarassed that they might seem uncool if they mention these names?

The second puzzlement I had was all the “by” credits of BMGPM, APM, WCPM, and De Wolfe Music. Turns out these are all companies that control massive music libraries and license music to people who need it, including movies and television shows. Although these institutions seem to loom large in this list, it’s like identifying a book not by the name of its author, but by the bookstore where you bought it.

The omission of the names of the composers also presents a practical problem: If a Bridgerton viewer hears a little scrap of music in an episode and wants to hear some more of that music, could they figure it out from this list? It took me a couple hours to track them all down, and I’m somewhat familiar with this stuff.

The first item on the list is identified as “String Quartet in B flat Major op 130 – VII Finale”. You can hear it at about 24:06 when streaming the episode over Netflix. Based on the opus number of 130, this one was easy: The composer is Beethoven. His Opus 130 String Quartet is also known as his String Quartet No. 13. It has six movements, so it might seem strange that the movement used in the episode is indicated as VII. Here’s the story:

The last movement to the Opus 130 String Quartet was originally a massive complex fugue called the Grosse Fugue, or Great Fugue, but it was so dissonant and difficult that Beethoven’s publisher was afraid that it would scare off potential purchasers of the score. Why buy it if they couldn’t play it? Beethoven was requested to compose an alternative final movement, and this is it. It turned out to be the last major piece of music that Beethoven composed before his death. The Grosse Fugue was published separately. (For more information, see my Complete Beethoven site, and particularly Days 355, 359, 363, and 364.)

Sometimes when the Opus 130 String Quartet is recorded, the original version is played followed by the replacement finale, where it’s listed as the 7th movement. But it’s not the 7th movement. It’s a different 6th movement. The error in the description on the Netflix site probably just reflects the erroneous information that BMGPM provided.

Here’s Beethoven’s complete Opus 130 String Quartet with this alternative ending:

The 6th movement used in the Bridgerton episode begins at 29:25 in this video. In reality, this music could not have been played at a Bridgerton ball because Beethoven composed it in 1826 and the 3rd season of Bridgerton seems to take place in 1815.

Next on the Netflix list is “Concerto for Violin, Orch in E-Major, Allegro Assai”. You’ll hear just a brief part of that music at 25:47 in the Bridgerton episode. This is one of Bach’s two Violin Concertos. It is also identified by a number in the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, the convenient numeric catalog of Bach’s music. This composition is BWV 1042. Here’s a performance on YouTube:

The music in the Bridgerton episode is the third movement, which begins in this video at 13:20. It’s unlikely that Bach would have been played during the Regency period because his music was in eclipse during that time.

Next on the list is “String Quartet No 8 K 168 IV Allegro”, which you can hear in the Bridgerton episode at 26:20. The single letter “K” is a major clue here. That refers to a catalog constructed by musicologist Ludwig Ritter von Köchel in the mid-19th century to bring chronological order to the music of Mozart. If you do a YouTube search of Mozart 168, you’ll find several performances.

Next on the list is “String Quartet in G Major”, a description that is not helpful at all. Lots of composers wrote string quartets. Joseph Haydn alone composed 68 string quartets of which 9 are in G Major. But it’s not Haydn; it’s teenage Mozart. This is known as Mozart’s String Quartet No. 3, K. 156. At 28:45 in the Bridgerton episode we hear some of the first movement.

The music listed as “String Quartet No. 23 in F-Major K. 590” — the last movement of which is heard at about 30:19 in the Bridgerton episode — is Mozart’s very last String Quartet, composed about 18 months before his death. Here’s a performance:

The last movement begins at 20:44 in this video, but the 3rd movement (at 17:06) is rather more interesting for its daring and unexpected chromatic journeys.

Next on the list is “String Quartet in B-Flat Major, K. Anh. IV, No. 210 – Milanese Quartet No. 2 – 1. Allegro di molto”. The letter “K” suggests Mozart, but this composition is listed in the section of the Köchel catalog labeled Anhänge or Appendix, part IV, which lists “doubtful works,” that is, music probably not by Mozart. The “Milanese Quartet No. 2” part of this description is mystifying: Mozart’s String Quartets Nos. 2 through 7 are called the Milanese Quartets, but this is not one of them, and the second of the Milanese Quartets (that is, Mozart’s String Quartet No. 3) is in G major. I suspect the description came from this YouTube video, which has the same bizarre error. It seems to be from an album called Mozart for Babies, which should probably be titled Doubtfully Mozart for Babies.

The final item on the Episode 2 list is “Piano Sonata No. 23 in F Minor, Op. 57 ‘Appassionata’: II. Andante con moto”, which is actually referred to in dialog in the episode. At about 32:34, Francesca Bridgerton (the third of the four Bridgerton daughters, who is celebrating her coming out) is asked what music she most loves. She responds: “Lately, I have been enjoying Ries. His Piano Trios are quite beautiful. And Beethoven’s Appassionata. I could listen to it forever.” (Listen to it forever? Like on auto-repeat in Spotify? What Francesca really means is that she can play it over and over because that’s how she’s also listening to it.)

Beethoven composed his Piano Sonata nicknamed the Appassionata during 1804 and 1805, and it was published in Vienna in 1807, so the score could easily have made its way to London by 1815. But the reference to Ferdinand Ries (a student of Beethoven’s who also served as his secretary) is puzzling. Ries’s first Piano Trio was published in 1811, the second in 1816, and the third in 1826. But Francesca’s familiarity with them is much less likely, and who would she have been playing them with? Even more puzzling is her interlocutor’s next comment: “I once heard a rumor the Trios were written to convey his feelings to Mademoiselle Ludwigs,” as if everyone knows who that is, and that such a thing is scandalous. If Francesca knew the music, however, she would have seen such a dedication right on the title page:

Anyway, when we hear Francesca playing Beethoven’s Appassionata at 38:23 in the episode, it is not the emotionally turbulent first or third movements that gives this piano sonata its nickname, but the more sedate second movement, a set of variations that builds with extraordinary calm and beauty, seemingly becoming faster in the third variation by shifting from sixteenth notes to thirty-second notes — that’s the part Francesca is playing — and then becoming calm again before heading without pause into the finale. Subtitles helpfully inform us “bright, elegant piano tune playing” because why should the subtitles actually reveal the composer and his composition?

Here’s pianist Shuann Chair playing the Appassionata on an 1820 fortepiano, so what you’re hearing is very much like what Beethoven’s contemporaries heard at the time he composed the music:

The second movement begins at 10:50 in this video, but this is one of Beethoven’s most famous piano compositions, so it certainly wouldn’t hurt to listen to the whole thing. Other performances on more modern pianos are also available on YouTube. Watch them all!

Because anybody who plays Beethoven’s Appassionata is automatically a Diamond.