Concert Diary: “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” at the Met

October 20, 2021

New York, N.Y.

Charles M. Blow’s 2014 memoir Fire Shut Up in My Bones is an unlikely source for an opera. To readers of the New York Times, Charles Blow is well known as a pioneer in “visual journalism". He became head of the Times graphics department in 1995, and continues to write a column on the Times opinion page.

But these achievements are mentioned only in the final pages of Blow’s moving and beautifully written memoir. Blow instead plunges deep into his childhood. Born in 1970, Blow grew up poor in Louisiana, the fifth of five sons and consequently nicknamed “Char’es Baby.” He’s a “quiet, introspective boy” who “could find no real place for myself in the world” and who “stopped running from loneliness and embraced it.”

Young Charles also struggles with his sexual identity. At first, this is something other people notice. There’s something in his gaze, something in how he occupies himself, something in his gait. But young Charles also has nighttime shadowy visions of male figures. This is all complicated by a traumatic event: When Charles is seven years old, he is sexually molested by an older cousin. As is sadly typical in such assaults, it is Charles who feels the guilt and self-loathing. He fears there is something about himself that invited the assault.

The sexual assault also triggers the memoir’s frame: When Charles is away at college, he learns that his cousin is visiting his mother. He rushes back home with a pistol ready to kill his rapist.

Composer Terence Blanchard has created an extraordinarily powerful and moving opera from this story of self discovery and reconciling one’s self to the demons of the past. Fire Shut Up in My Bones was first staged by the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis of St. Louis in 2019, and then opened the current season of the Metropolitan Opera.

Deirdre and I saw the penultimate performance at the Met last night. Here we are posing in front of a poster for the opera outside the opera house:

The final performance of the opera this season is on Saturday afternoon and will also be broadcast to movie theaters worldwide in the Met’s Live in HD series.

With this production of Fire Shut Up in My Bones, Terence Blanchard has become the first Black composer to have his work staged by the Metropolitan Opera. That this milestone has taken so long is quite astonishing. Not only astonishing but embarassing, even. Unconscionable, let’s say. In contrast, Anthony Davis’s opera X, the Life and Times of Malcolm X was staged by the New York City Opera 35 years ago. Interestingly, the Met announced just last month that X will be part of their 2023–24 season.

Terence Blanchard is primarily known as a jazz trumpeter and film composer. He’s been composing scores for Spike Lee’s movies since Jungle Fever in 1991, and most recently for the movies Harriet, Da 5 Bloods, and One Night in Miami.

Blanchard’s score for Fire Shut Up in My Bones effectively integrates his jazz roots with the skills that he’s cultivated as a film composer. A rhythm quartet (piano, bass, guitar, and drums) often percolates below the surface of the dramatic or emotionally touching moments, but then comes to the forefront in set pieces for a honky tonk, a gospel chorus, and a dance club. Blanchard has successfully integrated disparate musical idioms that effortlessly blend into a satisfying whole.

The libretto by Kasi Lemmons is quite faithful to the memoir. Many of us first saw Kasi Lemmons as an actress (Jodie Foster’s FBI bestie in Silence of the Lambs and a victim in the original Candyman), but she then graduated to writing and directing with Eve’s Bayou in 1997 and more recently, she co-wrote and directed the Harriet Tubman biopic Harriet,. Blanchard composed the scores for both these movies, so he’s been working with Kasi Lemmons for over 20 years.

One characteristic of memoirs is that the adult writer observes and sometimes even comments on their younger personage. Lemmons’ libretto mimics this by having the adult Charles (baritone Will Liverman in a career-defining role) share the stage with Char’es-Baby, sung by 13-year-old Harlem native Walter Russell III in his Met debut. They often even sing lines in unison.

Lemmons has also introduced two imaginary characters named Destiny and Loneliness sung by soprano Angel Blue, who has become a favorite of Met audiences. These characters interact with the adult Charles: Destiny urges him on the early scenes to confront his cousin (and by extension, his past), while Loneliness gives him comfort in his solitude.

The molestation scene in particular is handled with great delicacy by having Angel Blue provide narration. Rather than any overt visuals, it’s the words and music that give this scene its intense and harrowing power. Angel Blue also sings the role of Greta, who in the memoir becomes Charles Blow’s wife.

Kasi Lemmons has loaded the libretto with much exposition, but she has also used several verbal motifs that are repeated throughout the opera, such as “The south is no place for a boy of peculiar grace.” These become somewhat like mantras encapsulating the opera’s themes. What she hasn’t provided is the type of repetition suitable for traditional showstopping arias. Of course, this is not uncommon in modern opera. (I remember talking with someone who complained “Not one aria!” when the Met mounted Benjamin Britten’s Death in Venice in 1974.) But it would have been interesting to give the composer the chance to transcend the exposition. In Fire, Terence Blanchard writes for the voice is a declamatory manner that to my ears sounds very natural but also overly consistent, almost as if he’s reticent to revel in unabasedly emotional vocal lines.

Where the opera does pause momentarily are two extraordinary dance sequences by co-director and choreographer Camille A. Brown. The first is when the ghostly male figures that Charles sees in his dreams become alive and writhe around his bedroom. The third act begins with an astonishingly energetic step dance that brought roars of appreciation from the audience. Step is a type of dance incorporating stomping and syncopated body percussion that was created by enslaved people to compensate for the lack of drums. The tradition of step is continued at historical Black colleges and universities, such as Grambling, where Blow attended.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones has become significant in breaking down some boundaries at the Metropolitan Opera, but it is an opera great enough to be celebrated regardless.

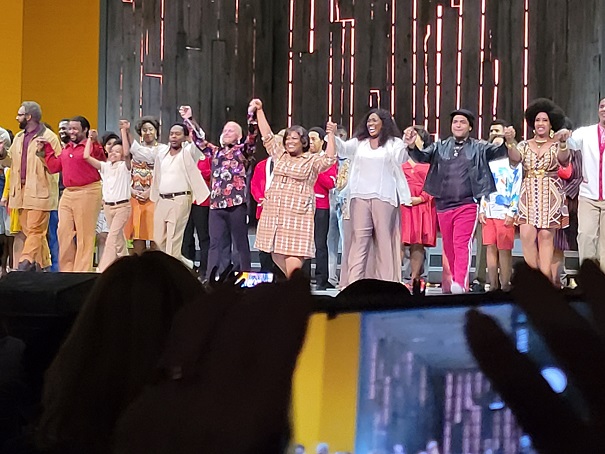

Here’s a curtain call I managed to snap over the heads of the standing and applauding audience. The white guy in the colorful shirt is conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin. To his right are Will Liverman and Walter Russell III, who sang the two ages of Charles. To his left are Latonia Moore, who sang Charles’s mother Billie, and Angel Blue: